By Sandra Morais

Cooking with Gas Stoves in the 1930s Lisbon1

Human practices of energy consumption transform and are transformed by social structuresi, an idea that embraces cooking as a social practice with profound implications on energy use. However, energy transitions are not made without appropriate converters, which was well understood by the Reunited Gas and Electricity Companies (CRGE), the local gas and electricity production and distribution company in Lisbon, when defining the commercial strategy. The diffusion of gas stoves in the Portuguese capital was slow, with different technologies coexisting at each moment. Most housing contracts at the end of the 19th century allowed the use of gas for cooking, but this technology would only spread faster from the 1930s onwards. The analysis of the advertising campaigns of the time shows, even if indirectly, the risks of gas stoves perceived by consumers and the strategies used to overcome this barrier. Concerns with appliance safety, the risk of poisoning, the quality and taste of food cooked on a gas stove, and the cost of town gas were addressed in the advertising discourse. In a way, some of these problems are again at the center of the current debate about gas stoves in the USA and Europe. Health and environmental risks are driving decisions to phase out gas installation in new buildings in some E.U.A citiesii. In Portugal, the ongoing energy transition and the goals outlined for 2030 in National Plan for Energy and Climate (PNEC 2030)iii, which require a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions between 45% and 55% compared to 2005 values, there is currently an intensification of electricity use in Portuguese households.iv In this context, deepening the knowledge about transition processes in the past can open doors to discuss the effects and anticipate evolutions in culinary practices, namely in Portuguese cuisine, an intangible heritage to be safeguarded.v

This essay summarizes the study of the impacts on domestic cooking practices from the knowledge transfer related to the transition from wood- and coal-fired cooking to town gas in early twentieth-century Lisbon. The analysis of magazines, cookbooks, cooking course programs, and advertising allowed us to trace some aspects of the transformation of cooking from the 1930s onwards. In the case studied we started with the advertising strategies of the gas and electricity companies, trying to find out what would have been the influence on the dissemination of cooking practices in a moment of transition to the domestic use of town gas. The programs and recipes presented in cooking courses offered by the CRGE, during the 1930s, in the city of Lisbon, were analyzed considering aspects such as energy transition stages, housekeeping ideals, and culinary literature of the interwar period.

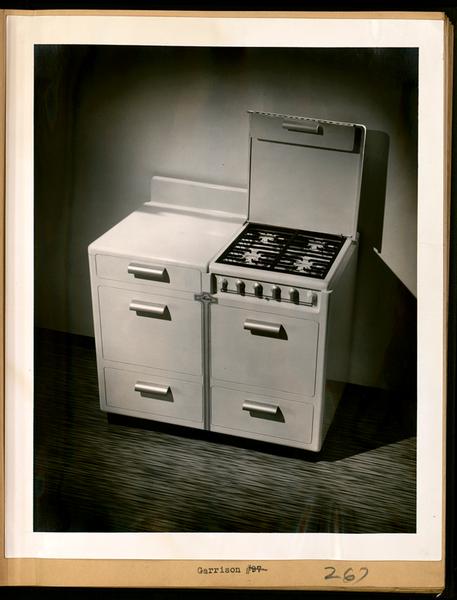

The diffusion of gas and electricity, together with the development of household appliances, the food industry, and a conception of domestic tasks supported by scientific and technical knowledge changed the domestic order. In the city of Lisbon in the 1930s, we find evidence that change was afoot, for example, in the discourse of domestic economy booksvi and in the advertising in the magazine O Amigo do Larvii (1932-1939), a propaganda magazine published by CRGE. A vision of the modern house and housewife was disseminated, guided by principles of hygiene and healthy eating, achievable thanks to the panoply of household appliances. In terms of cooking appliances, the gas stove was seen, at the time, as the desirable technology given the energy supply in the city of Lisbon and was recommended in cookbooks, for example, in Tratado de Cozinha e Copaviii. Although the electric stove is mentioned in O Amigo do Lar, the stage of energy transition and tariff conditions favored the expansion of gas technology in Lisbon.ix The diffusion of gas stoves in the capital was slow, and there were advances and retreats due to conjunctural conditions, with World War I being responsible for the energy crisis that slowed down the transition2 causing the return of firewood and charcoal to urban kitchens.x

In the 1930s the percentage of consumers who owned a gas stove increased significantly. In 1936 about 70% of gas consumers3 had a suitable stovexi. Contributing to this were the campaigns run by CRGE, which, like their counterparts in other countries, chose cooking to promote the use of modern energy in the domestic environment. The organization of practical cooking courses was a successful initiative to promote new technologies and ways of cooking. Traditional Portuguese cooking using firewood and charcoal (the predominant sources in the city of Lisbon and the rest of the country) was faced with an internationally influenced cuisine. The gas stove was presented to the housewife as versatile, efficient, predictable, and essential to diversify the diet. In the lectures of CRGE’s Cooking Courses, gas cooking was praised using several arguments, such as: it cooks food better; it enhances flavor, preserving nutrients and vitamins; it frees up time for other tasks; it saves on ingredients; it is more hygienic; it makes the kitchen fresh and clean; it is aesthetically attractive; and that it is safer and more suitable for kitchens with less space in modern buildings. xii However, the price of stoves was omitted as well as the loss of the winter heating function, so appreciated by users of fireplaces and wood or coal stoves.

The cooking courses were free of charge and took place once a week. In them, demonstrations were made with gas appliances for safe handling. The recipes executed in the classes of the 1930s were collected in booksxiii, an important source to analyze the culinary model chosen in these training courses. The 390 recipes from the Cookery Courses of the CRGE illustrate the trends identified in Portuguese culinary literature from the early twentieth century, highlighting the influence of French cuisine, the promotion of economy, and the rare reference to traditional Portuguese dishes. About 66% of the dishes use the oven for baking, grilling, au gratin, or bain-marie cooking. The most frequent cooking method is roasting (54%) followed by boiling in water (36%). Combined methods, requiring both burners and oven, are frequent. The dishes are fast cooking, averaging about 28 minutes to make.

Though it is difficult to measure the reach of these pioneering courses among the Lisbon population, they illustrate an interesting knowledge transfer initiative, even inspiring the culinary training model introduced in the mid-1930s in girls’ high schools. These cooking sessions fostered in the bourgeois class the idea of progress provided by access to new technology and food practices hitherto restricted to the professional restaurant/ hotel trade and the elite’s kitchens. This study allows us to conclude that the introduction of gas in the kitchen was one of the aspects to be taken into consideration in the change of cooking and eating practices in the domestic context of Lisbon during the 1930s. Finally, this study has highlighted the role of the sophisticated marketing strategies used in the past as facilitators of the gas transition and the associated cooking technologies. This conclusion raises a question about the relevance of using new marketing strategies when aiming at the phase-out of the gas stove and the adoption of alternative technologies.

1 This work was supported by FCT – Fundação para a Ciência ae Tecnologia (grant nº2022.11930.BD)

2 In 1914 the CRGE reported 37,690 gas customers, but from that date, the numbers decline to around 11,000 in 1920.

3 The resident population of Lisbon according to the 1930 Census (Direcção Geral de Estatística,1933) was around 594,000, and the number of gas consumers was just over 20,000 (CDFEDP, Statistics published in “O Amigo do Lar, April 1938).

iMadureira, N. L. (2016). Energy Transitions. Retrieved November 2020, from environmentandsociety: http://www.environmentandsociety.org

ii e.g., Karlamangla, S. (20230118). How the gas stove debate has played out in California. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/18/us/gas-stove-debate-california.html; Alund, N. (20230210). Federal agency is considering a ban on gas stoves in the US, report says: «Hidden hazard». USA Today Money. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/money/2023/01/10/gas-stove-ban-us/11022254002/

iii Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 53/2020.

iv Direção Geral de Energia e Geologia & Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2021. Household Energy Consumption Survey-2020. (Official Statistics)

v Resolution of the Council of Ministers (RCM) no 96/2000.

vi Brandão, E. (1937). Arte e Economia, Enciclopédia Caseira. Porto: Livraria Simões Lopes

vii CDFEDP. Companhias Reunidas Gás e Electricidade: O Amigo do Lar,1932-1939.

viii Maia, Carlos Bento da (1904). Tratado de Cozinha e Copa. Guimarães & Cª.

ix Bussola, D., & Teives, S. (2005). Domestic energy consumption. In Nuno Luís Madureira, A História da Energia, Portugal 1890-1980. Livros Horizonte

x Henriques, S. T. (2006). Os Consumos Domésticos de Energia em Portugal [Master’s Dissertation]. Universidade Técnica de Lisboa,

xi Matos, A. C., Faria, F., Cruz, L., & Rodrigues, P. S. (2005). As Imagens do Gás. As Companhias Reunidas de Gás e Eletricidade and the production and distribution of gas in Lisbon. Fundação EDP.

xii CDFEDP. Companhias Reunidas Gás e Electricidade: O Amigo do Lar,1932-1939.

xiii CDFEDP. Companhias Reunidas Gás e Electricidade: Programs, advertisements, and cookbooks from CRGE’s Practical Cooking Courses, 1932-1939.

Sandra Fernandes Morais is a Ph.D. student in Food Heritage: Cultures and Identities at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Coimbra, has a degree in Economics (1999) and a Master’s in Business Management – Corporate Finance (2009). She is currently researching the relationship between culinary practices, energy, and technological transitions during the 20th century in Portugal. She is a Ph.D. scholarship from FCT- Foundation for Science and Technology.

As a researcher, she collaborates with the Centre for History of Society and Culture CHSC-University of Coimbra and with the Centre for Research and Studies in Sociology (CIES-Iscte) of the Iscte – University Institute of Lisbon.