By Yuchen Zhao

Recent years have seen a revival of interest in the relationship between sites related to food production, distribution, and consumption and the social interaction within these locations in racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods. Food has figured prominently in the racialized public realm and the problems with migrants and minorities. Scholars interested in food spaces’ cultural and social significance generally focus on economic development, health benefits, and food access (Kelly et al, 2008; Song et al, 2009; Langellier et al, 2013; Young et al, 2018). Some focus on how cultural values, collective memories, and ethnic identities are embedded in the food landscape (Staub, 1981; Valle & Torres, 2000; Sutton, 2000; Sage, 2010; Coakley, 2010; Everts, 2010). Others examine how everyday practices in food spaces influence the formation of social ties and the framework of resistance within the neighborhood (de Koning, 2009, 2015; Roe, 2016; Leardini & Serventi,2016; Sen, 2019, 2021; Reese, 2019; Reese & Garth, 2020). Through the food spaces, scholars seek to better understand the conditions and experiences of racial and ethnic lives.

This short piece briefly analyzes one of the food sites, Cherry Street Community Garden in the Midtown neighborhood. Community gardens, as a site of contestation, not only offer land to grow food and extra access to fresh produce but also provide a unique space where residents gather together. Through urban commons such as community gardens, minority residents collectively produce space to resist, increase citizen participation, and build social capital (Ghose & Pettygrove, 2018; Dolley, 2020).

This study explores how gardeners from Cherry Street Community Garden utilize the gardening space to build social connections and trust between each other, as well as resist the everyday struggles, inequality, and injustice in a segregated and racialized community. Based on ethnographic research for Cherry Street Community Garden and the surroundings associated with the garden, this research explores how residents express care, love, and hope through the practice of growing, shopping for, preparing, distributing, and consuming food. This community includes an intergenerational group of African American gardeners who have tended a large empty lot that occupies an entire city block. Their access, choices, and consumption of food are bound by not only present conditions but past traditions and memory as well. They have roots in southern farming and brought memories of their parents or grandparents working on farms down South to their experience.

This study focuses on Midtown, a lower to middle-class, predominantly African American neighborhood (73% was Black or African American), in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The choice of Midtown has historical significance because this neighborhood has served as a “sanctuary” for displaced African Americans, homeless, and Southeast Asian refugees since the 1950s (Urban Anthropology, 2021; Nelsen, 2017 Encyclopedia of Milwaukee). St. Michael’s Church, a Catholic church constructed in the early 1890s, became a to the Danube Swabians at the close of World War II. It continued to serve as a shelter for homeless families and Hmong refugees after the Vietnam War, offering them food and social services. On the other hand, the urban renewal process turned the vacant lots and demolished houses into single-family homes, low-income apartments, and Tiefenthaler Park which provide more affordable living for middle-class to low-income families. Migrants from the southern United States and displaced residents from the nearby Bronzeville neighborhood forged a strong African American culture and heritage. The long traditions, such as forming active neighborhood associations or growing backyard gardens, connect people with strong cultural values, social meanings, and personal experiences.

During the summer of 2022, I did a series of field research associated with The Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures field school at the University of Wisconsin’s Department of Architecture. Field observation of community gardens and participation in weekly garden club meetings were my prominent method for exploring processes and meanings that people attached to the garden. I also conducted oral history interviews and short-form conversations with residents of Cherry Court and members of the Cherry Street Community Garden. I asked them to describe the physical and social character of their community, and they told me stories of their neighborhood.

Space for Social Interaction

Considering Cherry Street Community Garden as a microcosm of a community, the garden serves as an interactional space and a vibrant social setting. Sociologist Lyn Lofland (1998) describes such locations as “parochial spaces” where acquaintances and neighbors are involved in “interpersonal networks that are located within communities” (p. 9). While weeding, watering, or tending beds, garden club members socialize with each other. Social interactions in the garden decrease loneliness and isolation and enhance a sense of safety and community in the neighborhood. The network of relationships between individuals and groups around the garden depends on the communal social capital, specifically the trust and faith between the community residents, organization leaders, and participants.

To examine the garden as a social space, I analyzed the physical organization of the garden and the forms of interaction that take place in these spaces. The communal physical spaces encourage socialization, resting, contemplation, small meetings, and big celebrations. One can enjoy the garden view on a picnic table in the southwest corner, under the shade of a row of apple trees. Elderly gardeners sit on two benches close to the garden beds when they take a break (Figure 1). When weeding, watering, and caring for the garden beds, the gardeners socialize with each other. The garden layout enables routine social encounters; conversation is the main activity. The weather, the recent trip, the family visit, and the comparison between each other garden beds are all popular topics. Meanwhile, the large grassy strip on the south end of the garden accommodates large gatherings. The garden also offers a free library for the children of the community. The garden has spaces that encourage socialization, resting, contemplation, small meetings as well as big celebrations.

There are a variety of users in this garden. Gardeners meet neighbors and children from the nearby Kellogg Peak Initiative or the Penfield Montessori Academy. College students from UWM, MIAD, MSOE, and Marquette University spend time volunteering. Social workers associated with the Housing Authority of the City of Milwaukee, volunteers from the Hunger Task Force, church groups, and other youth-based organizations come to this space. Community gardens help to build a sense of community as they are a collective activity. For many volunteers who regularly visit, the activity of gardening is a critical way of interpersonal development, teamwork, and commitment. The garden provides opportunities for gardeners, volunteers, and visitors to connect, bridging weak ties, a term used by Nick Granovetter (1983) to describe relationships between acquaintances and strangers with few shared connections. Weak ties allow people to connect across diverse social networks, and in doing so, build strong social ties, create an inclusive community, and promote resilience.

To foster a culture of trust where all voices are heard, one must step back and ensure everyone’s voice is present. The weekly meeting of the Garden Club provides a platform for communications. Every Thursday, gardeners meet at the activity room in Cherry Court, an affordable apartment run by Milwaukee Housing Authority dedicated to low-income families, seniors, and disabled adults. Gardeners take this opportunity to connect and catch up. Leaders from BloomMKE, the nonprofit organization behind the community garden, always provide updates on garden chores. Gardeners also share their observations and concerns about the garden at the meeting. Additionally, the co-host of the meeting, volunteers from Lutheran Social Services, also offer activities and games to the gardeners that enhance their skills and knowledge of gardening and effective communication.

As has been demonstrated, there is a substantial value in community gardens to build social capital within and beyond the garden into the wider community and network. As different people attach collective meanings to the garden, social inclusion can be found as a motivation behind and benefit of the community garden, which is central to any plan which attempts to modify the environment in order to reduce or prevent crime.

Safety and Responsibility

There is evidence linking community gardens to improved safety in neighborhoods–that crime decreases in neighborhoods when the number of green spaces increases (Roy, 2008; Ghose & Pettygrove, 2018; Dolley, 2020). The Cherry Street Community Garden is open to the public at a wide range of times. Gardeners, volunteers, and visitors can drop in at any time of day. The openness of this unfenced garden may lead to some instances of theft and vandalism, even at a low probability. To prevent such incidents, surveillance and community policing are vital to make the Cherry Street Community Garden a very safe and social space. Even though there are no official surveillance and monitoring protocols, the residents who live close to the garden volunteer to do so. Some suspicious activities will also be discussed during Thursday’s gardener club meeting. Such collaborations assure mutual understanding and trust between community members.

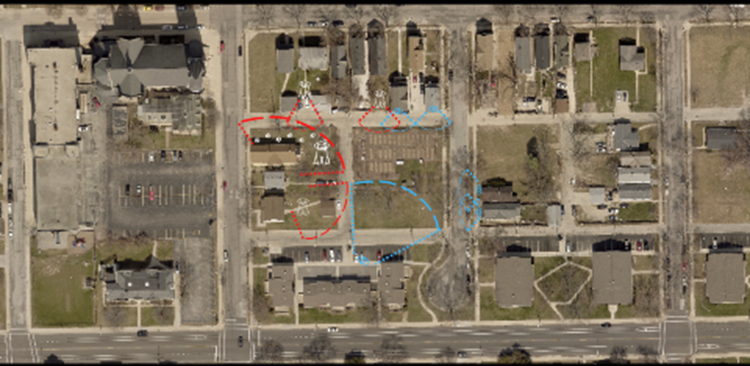

Visibility is vital to the success of watchful neighborhood surveillance practiced by community members. The map below shows how residents surveil the Cherry Street Community Garden and ensure everything is safe. Residential buildings, paved streets, and alleyways surrounding the Cherry Street Community Garden become sites of monitoring (Figure 2). A series of homes with porches and windows line the garden’s perimeter. Residents of these houses keep a watch on the garden. One gardener who lives across from the garden noted that she regularly sits on her front porch to observe the activities in and around the garden to ensure everything is safe.

Pet dogs also serve as a security line by carefully guarding their street. Three houses adjacent to the garden have guard dogs. These dogs bark at strangers passing by the paths and alleyways and alert residents to potential trespassers. Their barking produces a sonic atmosphere that indirectly ensures the safety of those in the garden and alerts the neighbors to any imminent danger in their locality.

As Jane Jacobs (1961) points out, urban neighborhoods can be safer with “eyes on the street.” When gardeners and residents are present regularly, it strengthens the space and inspires social cohesion around the community garden. The spontaneous surveillance and community policing may not directly reduce the number of crimes, yet they improve the vision of perceived safety in the community, encouraging more people to feel comfortable while navigating the neighborhood.

Rules and Regulations

Community gardens are inclusive places encouraging people to connect with each other and the land. Nevertheless, the inclusiveness of public spaces can sometimes deter users who may fear the presence of “undesirables” (Whyte, 1980). The Cherry Street Community Garden has established a set of rules of behavior and use for gardeners, neighbors, and children. At the first meeting, gardeners work with community organizations to develop a set of rules for the garden club. These rules are prominently displayed and posted throughout the garden perimeter and at the entrances. As discussed previously, there is no approach or force for the gardeners to enforce these rules, yet establishing the rules creates a collective sense of community. Furthermore, the perception of fear can also be influenced by the environment, such as the visualization of the rules.

A sign on the Southeast side of the garden describes the Cherry Street Community Garden Club and has information for those interested in renting a garden plot. There are sign boards at the garden entrance that list all the organizations that support this garden. Another sign near the apple and cherry trees forbids climbing trees and reminds users that the garden is a dog feces-free zone. A signboard in front of the “Free Garden” beds prominently displays the information that this free garden welcomes all community neighbors. The signs emphasize how community members cultivate mutual understanding and trust in their communities.

Conclusion

Since the 1980s, deindustrialization, long-term segregation, racial public policy, and governmental neglect have led to the constant struggle and challenges to the neighborhood, such as lack of access to healthy food, the overabundance of corner store and liquor stores, and reliance on fast and processed food. It reflects how structural racial food inequalities are hidden in the processes and policies that negatively affect this African American community. The garden is one of the answers in response to the decline and dissolution of the neighborhood. The Cherry Street Community Garden plays a central role for this group of African American gardeners in their experiences of navigating the food system. One of the garden’s fundamental goals is to address the lack of fresh fruits and vegetables within reasonable reach of residents who need them and to educate residents about food production and healthy eating. This garden intends to enhance a sense of community identity among the gardener and a sense of unity with the land at the same time. To gardeners on Cherry Street, the garden becomes a space of community empowerment and a ground of resistance and acts as the foundation of an enriched community collaboration, striving to turn the previous negative images of the neighborhood. As Reese (2020) emphasized, the space of resistance deeply engaged in refusal: “refusing to accept the boundedness of neighborhood spaces, refusing to give up hopes that another way is possible, refusing to allow the absence of supermarkets to completely define their foodways.” (p12)

To sum up, a rich internal network of associations has been maintained by developing a trusting relationship with the neighborhood residents. The way gardeners use the community garden’s physical spaces, the social interaction between gardeners, residents, and community organizations, and the mutual understanding of safety and responsibility give rise to the process of building a relationship of trust and accumulating collaborative social capital. Through the formation of social networks, the study examines the potential of such civic greening initiatives led by an African American community in inner-city Milwaukee. Collective understanding and trust are fundamental to creating a sense of resilience and resistance.

Works Cited

Aptekar, Sofya. “Visions of Public Space: Reproducing and Resisting Social Hierarchies in a Community Garden.” Sociological Forum (Randolph, N.J.) 30, no. 1 (2015): 209–27.

BeLue, Rhonda et al. “The Role of Social Issues on Food Procurement among Corner Store Owners and Shoppers.” Ecology of food and nutrition vol. 59,1 (2020): 35-46. doi:10.1080/03670244.2019.1659789

Britton, Marcus. “My Regular Spot: Race and Territory in Urban Public Space.” Journal of contemporary ethnography 37, no. 4 (2008): 442–468.

Coakley, Linda. “Exploring the significance of Polish shops within the Irish foodscape.” Irish Geography 43 (Oct 2010): 105–117.

Dolley, Joanne. “Community Gardens as Third Places.” Geographical research 58, no. 2 (2020): 141–153.

Enzenbacher, Debra J. “Exploring the Food Tourism Landscape and Sustainable Economic Development Goals in Dhofar Governorate, Oman: Maximising Stakeholder Benefits in the Destination.” British food journal (1966) 122, no. 6 (2019): 1897–1918.

Ewoodzie, Joseph C. Getting Something to Eat in Jackson: Race, Class, and Food in the American South / Joseph C. Ewoodzie Jr. Princeton ;: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Ghose, Rina, and Margaret Pettygrove. “Urban Community Gardens as Spaces of Citizenship.” Antipode 46, no. 4 (2014): 1092–1112.

Ghose, Rina, and Tom Welcenbach. “‘Power to the People’: Contesting Urban Poverty and Power Inequities through Open GIS.” The Canadian geographer 62, no. 1 (2018): 67–80.

Granovetter, Mark S. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” The American journal of sociology 78, no. 6 (1973): 1360–1380.

Lofland, Lyn H. The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory / Lyn H. Lofland. Hawthorne, N.Y: Aldine de Gruyter, 1998.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961.

Nelsen, James K. “Midtown.” Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, March 5, 2021. https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/midtown/

Pine, Adam Marc. “The Temporary Permanence of Dominican Bodegueros in Philadelphia.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 48, no. 4 (2011): 641–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009360687.

Reese, Ashanté M. Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. / Ashanté M. Reese ; Foreword by Dara Cooper. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Roe, Maggie. Editorial: food and landscape, Landscape Research, 41:7(2016), 709-713, DOI: 10.1080/01426397.2016.1226016.

Roy, Parama. “Urban Environmental Inequality and the Rise of Civil Society: The Case of Walnut Way Neighborhood in Milwaukee”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2008.

Sage, Colin. “Re-imagining the Irish foodscape.”, Irish Geography, 43(2) (2010): 93-104.doi: 10.1080/00750778.2010.516903

Sen, Arijit. “Food, place, and memory: Bangladeshi fish stores on Devon Avenue, Chicago.” In Food and Foodways, 24:67-88. Taylor & Francis, 2016

Torres, Stacy. ““For a Younger Crowd”: Place, Belonging, and Exclusion among Older Adults Facing Neighborhood Change.” Qualitative Sociology 43 (2020): 1-20.

Whyte, William H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Washington, D.C: Conservation Foundation, 1980.