by Joshua Rutherford

Joshua Rutherford:

This is Joshua Rutherford, Graduate Fellow at the Center for 21st Century Studies, and I’m here today, March 23rd, 2023, with Milwaukee-based artist Paul Druecke to talk about the relationship between food, land, and trust in his work. Paul, could you introduce yourself briefly?

Paul Druecke:

I have been a visual artist and writer for decades now with a practice in intentionally incorporates of variety of mediums. Some things that tie together my different projects are an interest in landscape, interest in, kind of, things that are easily overlooked, foraging and, and how some of those contextual elements relate to the kinds of cultural tropes, and cultural norms that we plug into as an individual and as a citizen, you know, and the expectations, I guess that come with those; and maybe we’ll have a chance to elaborate on some of that as we get into this.

Joshua Rutherford:

Yeah, so the reason we’re doing this interview today, the programming at the center this Spring is an interactive symposia series called Nourishing Trust, and it looks at the intersections of food and land trust in the present day. I think that your work fits into this conversation in a really unique way. So in thinking about the connections between food, land, and trust, our roundtables have touched on understandings from indigenous communities, farmers, and acad

For the last few years, give or take a couple of years, I’ve been increasingly leaning towards entertainment as a component of what and how I want to share as a creative person that, you know, is putting ideas into the world. My interest in entertainment was because of its relationship to the notion of trust. And, I don’t know that there’s a very like quick, easy read on that, but I do want to make a case, because coming out of a background that was perhaps more focused on fine art, a space where entertainment might not be seen as a preferred goal, and so for me to all of a sudden be like, oh no, I’m actually seeing that as this really valuable point of connection and point of engagement.

My work has always been very aware of how it will be encountered by the audience, and I want to be very generous in that. I think the idea of entertainment offers a particular dimension onto trust because artist and audience, I feel like, has an understanding of relationship. It gives a certain location in terms of, I know that I’m getting some type of enjoyment from this interaction. There is a kind of orientation, I think, that happens in offering someone an experience that they understand their role. The way it plays out in my projects, I feel, can be more direct or for like America pastime, I think, much less direct.

So that’s a good set up to maybe go into your, the question about America Pastime. America pastime started in 2020. It kind of comes out of a walking tradition in the fact that I, you know, just have a routine of going on walks for all sorts of reasons, it kind of feeds my creativity. Spring of 2020 was also the beginning of the pandemic. So, you know, a very kind of weighty cultural moment with a lot of stuff and a lot of unknowns going on. I like to think of America pastime as connecting the dots. It puts me in a very performative role, engaging with certain aspects of material culture. I’m always a little hesitant to just default to this word litter because I think it really predetermines too much about the relationship to these materials. I often describe them as orphaned items, leftovers, byproducts is a very helpful word. These things that are part of the waste stream. But when they’re kind of floating around on the ground and I live in River West, there is a lot of these items floating around on the ground. And so, if I’m going for a walk, there’s no avoiding the presence of these items.

emia, and I feel like your America pastime series brings a new dimension insofar as you’re exploring the relationship between food and land from a more environmental perspective. Could you explain the series America Pastime in your own words and explore how you think this series is drawing attention to the relationship between food and land in the urban environment?

Paul Druecke:

For the last few years, give or take a couple of years, I’ve been increasingly leaning towards entertainment as a component of what and how I want to share as a creative person that, you know, is putting ideas into the world. My interest in entertainment was because of its relationship to the notion of trust. And, I don’t know that there’s a very like quick, easy read on that, but I do want to make a case, because coming out of a background that was perhaps more focused on fine art, a space where entertainment might not be seen as a preferred goal, and so for me to all of a sudden be like, oh no, I’m actually seeing that as this really valuable point of connection and point of engagement.

My work has always been very aware of how it will be encountered by the audience, and I want to be very generous in that. I think the idea of entertainment offers a particular dimension onto trust because artist and audience, I feel like, has an understanding of relationship. It gives a certain location in terms of, I know that I’m getting some type of enjoyment from this interaction. There is a kind of orientation, I think, that happens in offering someone an experience that they understand their role. The way it plays out in my projects, I feel, can be more direct or for like America pastime, I think, much less direct.

So that’s a good set up to maybe go into your, the question about America Pastime. America Pastime started in 2020. It kind of comes out of a walking tradition in the fact that I, you know, just have a routine of going on walks for all sorts of reasons, it kind of feeds my creativity. Spring of 2020 was also the beginning of the pandemic. So, you know, a very kind of weighty cultural moment with a lot of stuff and a lot of unknowns going on. I like to think of America pastime as connecting the dots. It puts me in a very performative role, engaging with certain aspects of material culture. I’m always a little hesitant to just default to this word litter because I think it really predetermines too much about the relationship to these materials. I often describe them as orphaned items, leftovers, byproducts is a very helpful word. These things that are part of the waste stream. But when they’re kind of floating around on the ground and I live in River West, there is a lot of these items floating around on the ground. And so, if I’m going for a walk, there’s no avoiding the presence of these items.

Paul Druecke:

In terms of connecting dots. There’s just the idea of these materials, these leftover unwanted things. But there’s also each particular instance of that Cheetos bag and that plastic lid and that red straw and that mylar balloon, like each of those is a dot, I am a dot in this process, and I think of all the people as dots. Whether or not you pay attention or are aware, this is part of the environment that you are moving through. Maybe in my performative role, I’m a bit of a proxy. But I, you know, I do think everybody is kind of implicated in this scenario. The many different types of cultural norms and cultural systems are dots in this that I look to America past time to kind of connect and reference those and bring those into the discussion. Obviously, the land is a dot in this scenario. The economy and the economics that drive these things are part of the dots. Besides this kind of performative role where I’m out in the walk, engaging with this litter, perhaps picking it up, perhaps staging still lifes and, or photographing with it, I’m also writing about it and often that takes kind of poetic leaning and that is also one of the dots. So I start there just like there’s a lot of variables going on.

Joshua Rutherford:

It’s a full cosmos!

Paul Druecke:

Much of America pastime ends up being shared via social media platforms, in particular Instagram. And that is very intentional as a way to kind of take this material that I think very few people would think of as entertaining in any capacity but try to find a way to put it in a new light. The one thing I would, that I would say, I mean, I’ve been around for a while, as a child in the seventies and the ego consciousness that was starting there and the TV commercials that were being run and a kind of societal awareness and watching that discussion kind of play out over the decades. Nothing has, you know, in terms of me going out on a walk and what I’m going to see, it hasn’t changed and if anything, it’s gotten worse. And I’m curious what, if anything, kind of changes the equation for these byproducts and how prevalent they are.

When the project started, and really, it wasn’t a project, it was a response to a huge cultural shift that was going on where we weren’t going to be socializing with our friends or family because of COVID. It was a way of seeking out some connection on my walks. Like, okay, that Cheetos bag, somebody was using that a few hours ago or a few days ago. I mean, that sounds a little macabre, but those were also pretty extreme times. And kind of slowly, the substance, or the fact that there is substance here, kind of slowly occurs to me. And then two years in, I’m like, oh, that’s my litter. And I want to kind of take ownership of it because if there is any collective resource, I mean, that’s it, it belongs to all of us. Not necessarily a pleasant thought but is there some potential that we’re not aware of because, you know, we prefer to ignore.

And I think another thing that’s is absolutely part of, but largely unspoken, there’s a lot of people that are thinking about and aware, and the kind of default when you encounter free floating orphaned items is that they don’t belong there, they belong in the sanctioned waste stream. But you also have to realize that it’s basically picking the Cheetos bag up from, you know, that patch of buckthorn and putting in a big hole with a bunch of other stuff, the material weight of that on the surface of the planet kind of remains the same. And so there’s no easy answer, but that’s where like part of the dots become the larger infrastructure that turns this stuff out and, you know, yes, we can move it into the landfill but it doesn’t solve some of the underlying reality of what happens on the surface of this planet, over the next 100 years, over the next 1000 years.

Joshua Rutherford:

It doesn’t change the fate of the garbage in any way. In both scenarios, you know, I mean, the buzz is all about microplastics.

Paul Druecke:

Yeah, so we’re aware of, you know, like this is now in our drinking water. It’s in our agricultural soil. Of course, you know, it doesn’t degrade quickly, but it does degrade. America Pastime is obviously not solving all of these things, but by connecting the dots, it is looking for some new perspective.

We should connect this to some of these questions of food and trust and land because America Pastime is about all sorts of byproducts, but I would say the vast majority of them floating around the neighborhood of River West are from the food industry, because of our commitment to that convenience. And if you want to think about trust, the packaging industry does a really amazing job at delivering these products in a way that we trust so that when you go into the store and you buy two for $1 bags of whatever salty snacks you want, and you open them up, you’re reasonably assured that that is going to be fresh, and crispy, and salty and, you know, that product is going to be exactly what you’re expecting it to have. And that packaging is going to carry the brand that the corporation wants it to. The trust that is created on certain aspects of packaging design is, you know, like A+, A+++.

Joshua Rutherford:

It’s that reliability of being able to find it the same way in every environment.

Paul Druecke:

Yes! And it, you know, it makes it affordable for them. It’s affordable in many instances for the consumer, but it’s created a certain path that we find out that, you know, the human species just loves single-use packaging that you don’t have to think about ever again. Like, you open the bag, you consume it and then you’re done with it.

Joshua Rutherford:

No dishes, nothing to worry about, it’s pure enjoyment.

Paul Druecke:

No dishes, yeah, you’re not getting your chips in a glass jar. I wanna generalize here, like, all levels of consumer society benefits in ways and connects to that convenience and that lifestyle. And it’s hard to imagine shifting that.

But kind of some imagery, that I’ve created for myself, is this notion of a value cliff. And it’s like all of the engineering and the design and the infrastructure that creates that Cheetos bag, like that front-end investment; we’re so good at that! And it creates, you know, what is that bag worth? Like when it holds your chips, it’s invaluable in a way, but let’s just say it’s worth $2.50 and you open it up and you eat it and that bag falls off the value cliff, maybe into the landfill, maybe, you know, into onto the beer line trail. And it’s now the value is, is not just zero, it’s like negative value. And that’s where I think another good thing to acknowledge, in terms of looking at this thematic focus of food, land, and trust, is just how tricky the notion of trust is. It’s such a delicate phrase because it’s so easily abused and it’s so easily manipulated once you have somebody’s trust. I feel like the food packaging industry does such an effective job on the front end, and then all of a sudden we’re not even thinking about like, okay, now we’re left with this item. Where does that belong? What is, you know, what is its value?

Joshua Rutherford:

Yeah, we don’t think about the place of items like that, we think about the contents, but you’re right, there’s this material artifact that’s just created for the exclusive purpose of being discarded.

Paul Druecke:

Again, this is where connecting the dots; we’re all part of not wanting to second guess whether a recycled bag is actually sanitary. There’s an anthropological component to connecting the dots kind of a sociological component to trying to connect those dots. I want to connect this to some sense of entertainment to see my role as slightly performative. This spring I’m gonna be rolling out a series of tours to invite people to join in the process of trashing, wanting to kind of share my experience. Like, is there an audience, you know, is anybody interested in some of these insights? And I would be the first to own that it’s not necessarily an easy sell, for one person kind of grubbing around to be like, no, wait, you need to look at this. Certainly, then puts the ball back in my court in terms of like, now there’s more eyes going to be looking at this. Can they trust what it is that I have to offer?

And the idea of the tours came from somebody being like, I just want to be with you because I wish I could have that perspective as opposed to just being frustrated or angry that litter exists. And I mean, and I understand that’s an easy place to go to, but also it just changes nothing. You know, we, we’ve got six or seven decades of frustrated and angry with nothing changing. I was in Berlin last year and got to meet my first Instagram friend, like somebody who I would have only met because we connected via things that were being posted, Suzanne Soldan, who is a dancer and urban choreographer and interested in the landscape. Susan, in particular, was just like, I look at this and I, I’m just not sure how I’m supposed to respond; like they’re funny, they’re aesthetically pleasing, like they’re jarring, they’re, you know, they’re sad and it really plays into how I think about entertainment where now somebody is looking at something getting very particular feelings from it. Like this combination, sometimes the way things collage together can be humorous, can be poignant, and in having to question their responses, they’re locating themselves in relation to America Pastime, back to this idea of connecting the dots.

Joshua Rutherford:

Other recent work of yours is also related to food, your video series, Milwaukee Kitchen and Kitchen Minute, are both exploring relationships with food through new lenses. While perhaps not the direct focus of these works, I think that both require a certain level of trust, between guests and hosts in Milwaukee Kitchen, for example, and between participant and artist in Kitchen Minute. Could you briefly explain the Milwaukee kitchen series and elaborate on the role of trust in these videos?

Paul Druecke:

I absolutely want to carry over that thread of entertainment, and in a way Milwaukee Kitchen is a little more straightforward, in that the original Milwaukee Kitchen series is set up as a cooking program. It streams on YouTube. It really offers some kind of familiar structure that, you know, people turn to when they want to be entertained. So this connection and using that entertainment to build trust will come up as we talk about some of the details.

I say cooking program, that’s the format that it takes, but the emphasis is really on kind of serving up hospitality and serving up the kitchen as this social space. And I love, just the idea of, you know, when you think of domesticity in this kind of larger sense, if there is a kind of trustworthy heart to domesticity, I mean it exists in the kitchen, the place that we turn to to feed ourselves. And so I think there’s a lot of symbolic layers and importance that go to that space to begin with, that becomes the background.

The basic structure is there’s a host, busy doing something in the kitchen, and then an unexpected knock on the door and somebody is dropping by. That person comes in and they get kind of pulled into whatever was going on in the kitchen; maybe they’re making some food, maybe they’re talking, maybe something is broken. As they’re getting into a little something, there’s another knock on the door, somebody else is dropping by and that is going to repeat X number of times over the course of an episode, dramatizing something that does feel like it’s part of this neighborhood. This is also produced in River West.

Paul Druecke:

It’s set up to be a little over the top with how it portrays that hospitality that you know, I think is one of the great things about entertainment is the way it can use and push things in this drama in a dramatic form to make their point. You know, nobody’s dropping by anybody’s house in 2023 without texting them, you know, three times between leaving their home and arriving at their door. But it happens all the time in Milwaukee Kitchen, people have been dropping by for many years. We’re finding a dynamic effect with more people wanting to drop by, and I feel like that is, for me, a kind of successful outcome of wanting to share this space, wanting to share these conversations, is people coming across it and being like, oh, I want to be in that space or I want to be part of that conversation.

Milwaukee Kitchen grows out of a love of cookbooks, as well as that kind of domestic space, but this idea of these books as practical manuals, but also as these cultural artifacts spanning back now not just decades, but centuries, and being able to kind of dip back in time, or you know, see what was trendy 10 years, or 20 years ago. It’s also the kitchen and the cookbook I think is like one of the more comfortable spaces to think about like some of this cultural hybrid and cultural fusion. Where we’re sourcing our spices, what kind of different flavors do we want to bring in.

Paul Druecke:

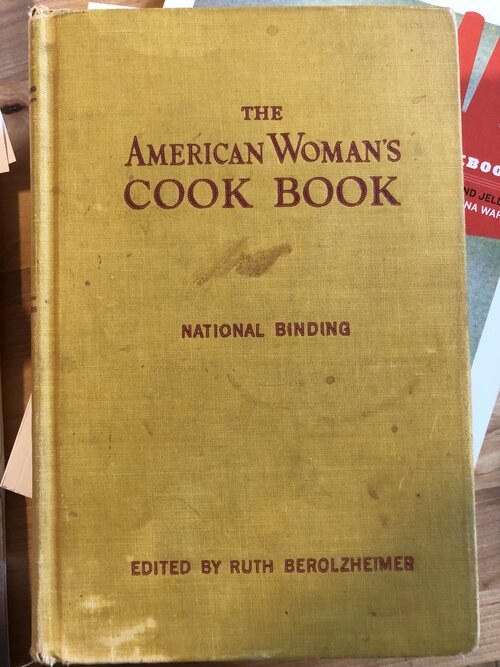

One particular, I should just call this out, I inherited the American woman’s cookbook for my mom in the late nineties, it was published in the late forties. My mom probably got it as a wedding gift, but it feels like it was maybe in the 11th edition at that point. And it feels like the 19th century in terms of what’s in the pages, like this manual for slaughtering animals and taking the feathers off of your chickens. And, you know, so you get all of that information, also recipes that feel like they’re from another planet in a way, in that time frame. And it just kind of honed me into all of the information that is in there. You know, this is something I hadn’t been thinking about, but because that cookbook really invites questions about: Do you trust the author is, you know, like, have they put things together in a way that’s going to give me the desired outcome?

And I want to kind of build on that, because, you know, we’re thinking about these ideas of food and trust and, of course, in the kitchen, you know, you want that to be a very trustworthy space where if you’re sharing food or eating food, being shared with you, you’re not going to be sick because of that. You know, so that is very relevant role for trust and building trust. But Milwaukee Kitchen is also again, in this emphasis of the social is like, can we trust this as a space for conversations to organically unfold.

I also think Milwaukee Kitchen does something really, really nice with this notion of time. And this is something that gotten some nice press coverage, the Milwaukee Record referenced Milwaukee Kitchen as the “antidote for the modern cooking program (and everything else),” which, you know, that’s definitely some big shoes to fill in terms of trust, but very thankful. But there was someone who recently was like, I tend to be anxious in the kitchen and I start to watch an episode of Milwaukee Kitchen and I’m like, hurry up, you know, get on with it. I’m wanting things to move quicker in the kitchen and then by the end of it, I’m like, oh, you know, this a more relaxed space. And I mean, that was just so welcomed to hear that sharing our idea of kind of being in this space together would kind of spill out and reverberate in how somebody thinks in their own space and their own time in their kitchen when it comes to prepare their own meal.

Milwaukee Kitchen has, you know, it has evolved, it has needed to evolve. Not quite three years in, we hit the COVID, where like the idea of inviting somebody over to your house wasn’t going to, it took on a whole new meaning. And it’s like, well, is this relevant? How is it relevant? And what happens in the COVID episodes is this highlighting a notion again, the slightly over the top dramatized notion of synchronicity of people all coincidentally in their kitchen at the same moment, chopping onions for incredibly different dishes. And that was fun to kind of put that together and think about everybody in their own spaces.

And I went off on the tangent to get back to Kitchen Minute, where this spinoff series is like much briefer, short, little snippets, but an opportunity, a platform for people to share some moments where they’re in their own kitchen, cooking food, thinking about a process. I mean, at that point, it becomes hoping and wanting to build trust with the audience for them to interpret that invitation as they would like. So now we’ve done two batches of the Kitchen Minutes, and that invitation is open, but we are still very actively in the role of building trust where someone encounters this idea of an invitation to share and then feels comfortable following through on it. That is a very nuanced and a very complicated process given everybody’s schedules, and everybody’s busy and, and I, you know, just would acknowledge and use this as a platform to, you know, say we really continue to work on extending the invitation and kind of building up that trust.

Joshua Rutherford:

Yeah, I think that sort of participatory element of Kitchen Minute makes it particularly interesting to think about the concept of trust. You’ve kind of made a career of doing this sort of participatory work.

Paul Druecke:

When it’s a kind of integral, I mean, a big project would be A Social Event Archive, that was inviting people to contribute snapshots. I want to say certainly over the years, I don’t default to participatory. It’s very complicated and nuanced and maybe some of those complications are of trust and where trusts blur into something that feels maybe slightly manipulative. So wanting to know exactly what’s being asked and being very intentional and owning that whole process.

Paul Druecke:

There was a moment in the art world, you know, like maybe a decade after I was kind of really focused on A Social Event Archive, where this notion of social practice and the interaction and the invitation was really, really important. And I recalibrated my role as I was seeing it kind of take on this larger role in this discourse and not always being comfortable with how that was being deployed. And you know, sometimes it’s nice when the artist just owns it; like I’m responsible and here it is, you can consume it as you as you will and you don’t have to do anything except for be. But with Kitchen Minute, and the fact that the kitchen is such a fascinating space, the centrality of the kitchen in keeping your biological self alive is important and it felt like it really warranted moving out into that open invitation again.

Joshua Rutherford:

Before we conclude our interview, is there anything else you would like to add?

Paul Druecke:

Just maybe back to the idea of connecting dots, you know, I think both projects are trying to connect dots. Both projects exist on social media and Instagram, and one way to connect dots, if anybody is hearing this and is interested, there’s Milwaukee Kitchen on Instagram and then my name Paul Druecke on Instagram are ways to find me, and I would love to hear from people about some of these ideas and or continuing conversations. It’s very much part of the substance of this work. Thank you, Joshua.

Joshua Rutherford:

Thank you, Paul, this has been a wonderful talk!

Check out the most recent episode of Milwaukee Kitchen below:

Paul Druecke is a multimedia artist that has been working in Milwaukee for decades. His work has ranged from painting and sculpture to participatory art projects and poetry. Druecke’s work has been featured in many arts publications around the world, including his Social Event Archive being exhibited at the Milwaukee Art Museum, and he was featured prominently at the Whitney Biennale in 2014. Druecke’s work presents us with a unique perspective of Milwaukee’s history, the way Milwaukeeans produce meaning in their relationship with public spaces, and how the diverse residents of our fine city form community. He was recently named one of Milwaukee Art Board’s Artists of the year.

Joshua Rutherford is an art historian, educator, and advocate for social change. His research in Art History privileges community reception, collective representation, and political activism using methodology rooted in performance studies, affect psychology, and media theory. As an educator, Joshua is passionate about inclusion and strives to create a learning environment in which ideas can be discussed, challenged, and otherwise explored from multiple perspectives. He believes in learning through experience and strives to create projects that help students connect their personal work to the canon of art history.