By Baishali Ghosh

Dak (ḍāk).

In many south Asian languages—such as Bangla, Hindi, Assamese, and Urdu—the word dak indexes ‘calling’ in textual, sonic, and material representation. It has an intrinsic connection with the ideas of travel, the willingness to connect, and connectedness urging us to call. In Bangla, we say deke galo (someone called and went) or dak diye jay (going by calling). This act of calling with an urge to connect finds beautiful embodiment in the house called dak ghar (post office), the object called dak (letter), and the act of calling (dak). Dak also suggests the call of death, the departure for post-life, and the afterlife.

Rabindranath Tagore’s play Dak Ghar (1912 & 1965), which features still and mobile lives with multiple narratives in time, inspired us to conceptualize our Dak project during the pandemic. In the play, a window frames the inside and outside world of Amol, a sick and lonely child. Observing his incurable sickness, his physician isolates the child in a room. Thus, sick Amol experiences the outside world’s time, sounds, and smells through the window beside his bed. He sees various people pass by his window. They are the curd seller, the watchman, the village headman named Panchanan, Dada-Thakur in the attire of a fakir, a flower seller named Sudha, a flock of boys who work in the paddy field, the blind man named Chidam, and a wanderer in his classic nagara shoes. He starts chatting with them, and they share their daily tales with him. Thus, Amol is told of a new post office in his village. The little boy believes that the king will write a letter to him. Expressing this to his window-side friends, everyone comforts the sick boy by saying he will receive the king’s letter one day. Amol lets his fantasy fly with the king’s imagined letter traveling across the villages, mountains, rivers, and paddies to reach him; he waits and keeps asking his window-side friends about when the king’s letter will arrive. Seeing Amol’s deteriorating health one day, the compassionate village headman gives a fake letter to console the boy. As Amol cannot read, he informs Amol that the letter states that the king will soon visit his house. Somehow, Amol’s desire to meet the king reaches the monarch through an anonymous messenger, and the king sends his royal physician to the boy. But it is too late, as Amol has gone to sleep forever.

However, refusing to be lonely like Amol, we conceived and curated our space of belonging by ‘calling’ (dak, henceforth) our human and non-human friends. The dak project draws upon our discursive creative practices, connecting our lives with tangible and ephemeral objects and people that never let us be lonely and lost. We pushed the idea of dak in the historicity of artistic practice and material. Our narratives travel back and forth through times, places, and histories which constitute our identity and collective exploration.

COVID-19 radically called for changes in our daily conversation. Indeed, it challenged us to delve into the complex social and epistemic practice of connecting and addressing isolation. Tracing those practices of dak allowed us to be disobedient and unruly with our ideas and imagination; we witnessed fluid exchange, curiosity, interpolation, blunder, broken periods, and numerous surprises in the process of breaking quarantine. Image-making in the Dak project is not just a way of translating ideas and imagination; itoffers epistemic tools to think through the complex and collective anxiety of diverse isolations.

The Dak project continues to assemble the interconnected social and environmental relationships that embrace the immediate and mutual; thus, we still long to hear and share and travel forward in time. We also revisit the turning points, poignant moments, vulnerable survival, and dismay of being abandoned in the pandemic phase.

Lockdown

Ramheube Riame

When Ramheube Riame was ready to travel from Haflong to Hyderabad, crossing approximately 2700 kilometres to study at the University of Hyderabad, the strict lockdown of COVID-19 was an utter shock for him. The lockdown was buzzing with the question, ‘what is this isolation’? What are the possible ways to decipher this isolation from the isolation of his small village in Haflong in India’s northeast, with a thin connection with the rest of the country, always experiences? Ramheube Riame is a Zeme Naga, a tribal community living in Haflong, Assam. His work titled Ku la delei (‘calling’ in Zeme dialect, Figure 1) is a take-on of Hepau-paupeu (a person who delivers a message by calling people). Riame grew up seeing Hepau-paupeu conveying messages. Hepau-paupeu called out the names, gave the news, and left for the next destination. His messages would be about arrivals, departures, births, deaths, marriages, illnesses, gains, losses, and so on. Hepau-paupeu also delivered news of weather changes as the Zeme Naga community cyclically migrated for agriculture, known as jhum cultivation.

In between 1968 -70, the dak ghar (post office) was set up in the neighbouring village, named Leiri (of the Hmar tribal community), to provide the service for five to six nearby villages, and hepau-paupeu would announce if anyone’s dak (post) had arrived. Hepau-paupeu was the contact for the community network of anthropologists, photographers, and researchers starting with British anthropologist Ursula Graham Bower’s first visit in 1937. Ramheube Riame says that mobile phone connection has replaced Hepau-paupeu’s work. His works share multiple visions of calling and the scattered belongingness within the act of calling. Riame’s Ku la delei is a layered reconstruction of this essence of calling. It depicts a chiaka (bag) cast in cement and iron. He adheres to the naturalistic representation of the chiaka that Hepau-paupeu used to carry. The Zeme Naga community still uses such chiaka during their travel. He installs itin several site-specific works, such as his recent work Tat timradibe Leuruak (‘Ballad of Dislocation’) in Hyderabad in June 2022 to resonate his community’s cyclic migration and farming. Thus, Riame’s Ku la delei presents visual and conceptual connections of the multiple isolations he has been subjected to.

Susmita Yadav

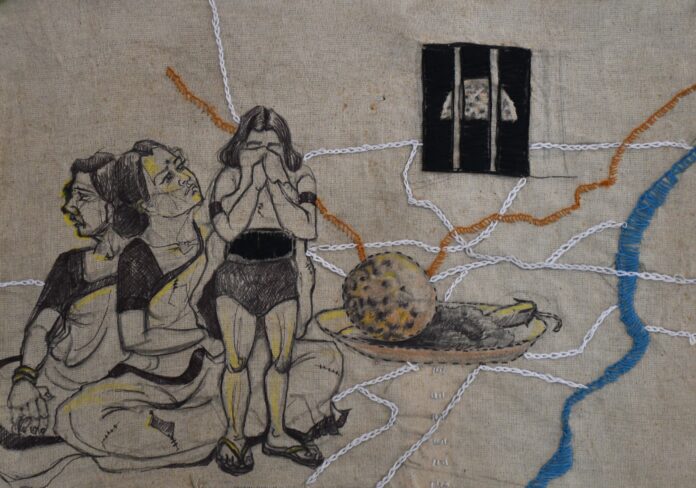

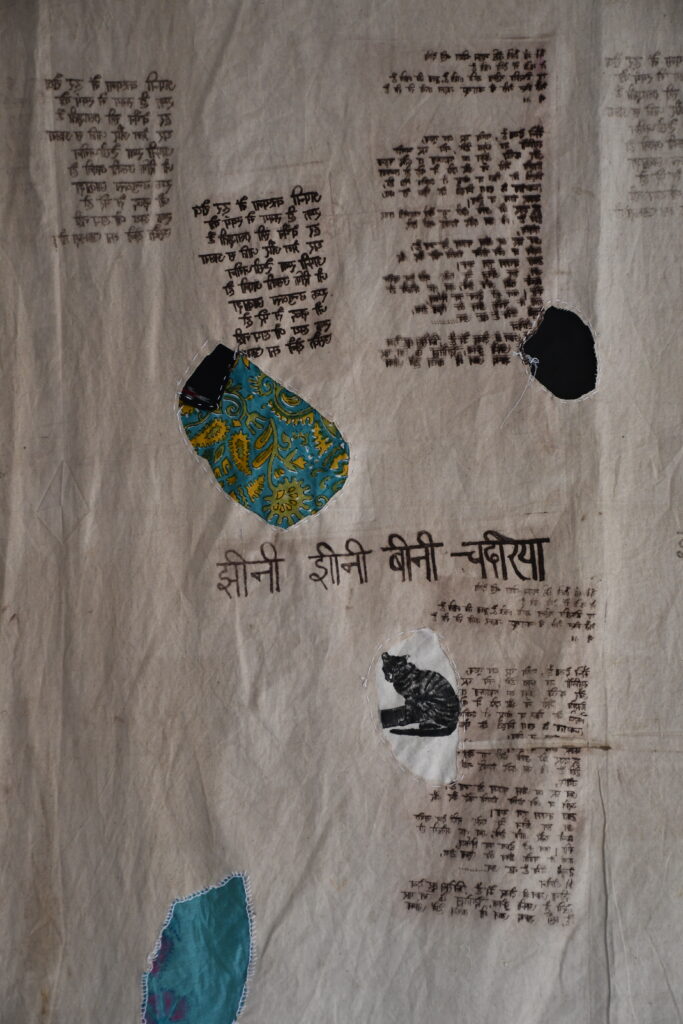

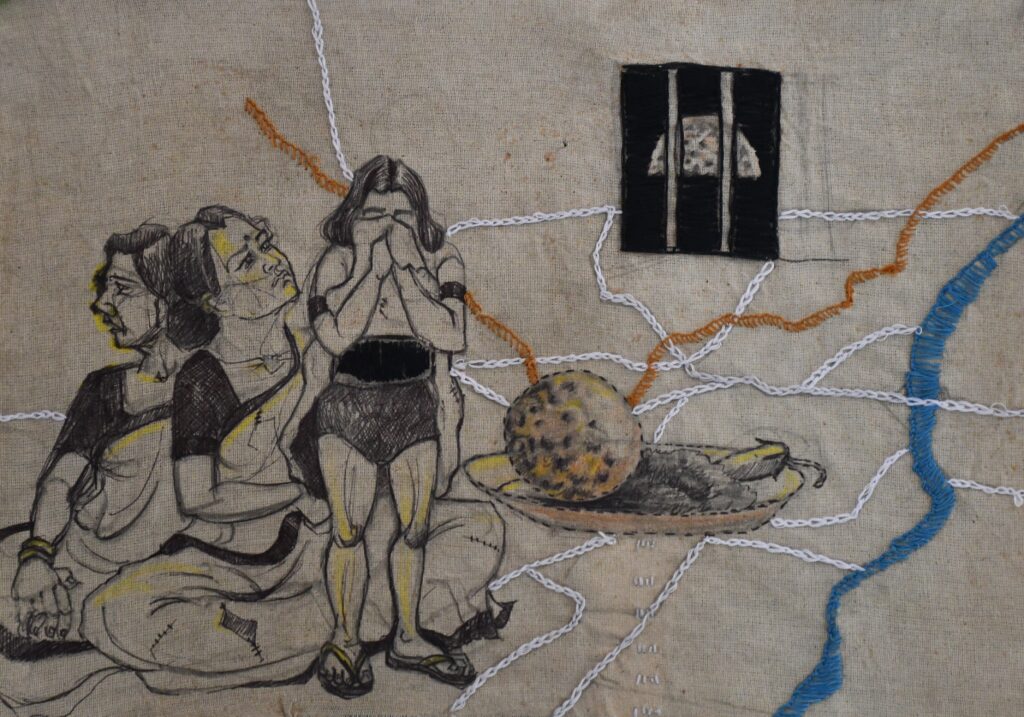

The lockdown amplified Susmita Yadav’s days with the sounds and gossip of family members with whom she grew up. Her kin, such as her mai-mausi-didi-chachi-dadi (mother, in-laws, aunt, sister, cousin, niece, and grandmother), are threads of herseries jhini jhini bini chadariya (quilting intimate stories). She weaves the Bhojpuri women’s tales connected with the sounds of cooking, washing utensils, household chores, chuckles, and cries (Fig 2 & 3). In her work, she revisits her experiences growing up with the Bhojpuri women through khudai-bunai (darning and needling) and chap (printing) on cotton. The window appears as a metaphor for networking where exchange, expression, and accumulation happens in pieces (Fig 3, 4 & 5). Thus, windows operate as architecture, social media screens, and mental spaces in her work. Even a torn part of a woman’s sari–pallu, often worn over the head or shoulders, appears as a window for Susmita. When their sari–pallus are worn into pieces, Susmita joins them on her cotton in jhini jhini bini chadariya.

Jhini jhini bini chadariya is a line from the legendary poem of Kabir, a 14th -15th-century saint, poet, and weaver. Bhojpuri women hum this line along with the kahe ka tana, kahe ki bharni (warping taunts and teases) during their domestic drudgery. Susmita juxtaposes Kabir’s poem with Nirmala Putul, a contemporary poet from the Santhal tribal community in Jharkhand (Fig 2). The verses are not visible from a distance; one must bring the cotton near the chest to read the poems. The chain-stitched threads that run on the cotton are not just an artistic process of the work but also suggest the rhythm and pace prevalent in both Kabir and Nirmala Putul’s poems.

Furthermore, charcoal is an ingredient of kajal (collyrium/ kohl) in women’s sringara (embellishment for a particular purpose); charcoal is also a fuel for their cooking. Susmita’s charcoal drawings and texts (Fig 2, 3, 4 & 5) entangle the sringara and survival of Susmita’s mai-mausi-didi-chachi-dadi. Ultimately, she darns the image of the quilt, draws the pile of aged fabrics on a chair, and designs the window as a picture frame, much like a still life study (Fig 4). Indeed, she cracks the typical still life drawings by evoking the idea of sound embedded in the line jhini jhini bini chadariya.

Kaustav Chatterjee

The COVID-19 lockdown granted Kaustav Chatterjee a long vacation that he kept postponing. Growing up in a middle-class joint family where the children rush and run with the rhythms of the schooling system, his adventures, like those of Tom Sawyer and Peter Pan, remained incomplete. Kaustav Chatterjee’s handcrafted diaries, which he calls Roj Namcha (daily tales; Figure 6), and Mejobabu’s Diary (Figure 7) are accounts of his long vacation of lost and leftover imaginary adventures with his nonhuman friends.

Chatterjee’s drawings unlock his adda with his friends, who are fish, photos, advertisements, and many such things which live with him in the grey areas of his nascent artistic practice, areas which are intimate, isolated, and fragile. The pages of his diaries tell his stories with living and non-living things. It reminds us of Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘Sahaj Paath’ (easy learning), a part of every Bengali kid’s childhood because of the fluid and easy conversation between the human and non-human world and the alphabets of Bangla. One of the pages from Sahaj Paath’ reads “hrôsshô-u dirghô-u; Daak chhare gheu gheu”; it means hrɔʃʃo u u̯ – dīrghô ū (which are fifth and sixth vowels in Bangla); Doggie does bhow-bhow. Chatterjee experiments with his handcrafted diaries as a sequel of Sahaj Paath to ease up with difficult times. His words and images on the pages are in plays like the rhymes in Sahaj Paath. Thus, Sahaj Paath offers him poetic ways to converse with non-human elements living quietly in his closets. Chatterjee’s Roj Namcha (Fig 6) is a list of remains. The remains include photographs, torn wrappers, drawings, and many dak naam (the names used to call someone or something). His passport-sized black and white photos of identification documents are standard in a schoolbook and a ration card, and frequently appear on the pages of Roj Namcha. He juxtaposes his photographs in his teens with his father’s and the paternal uncle’s photos in their teens. By collapsing age differences of family members and the timeline of photographic materiality, they meet to ‘recollect’ stories of youth which they had in different times and locations. The mundane and broken drawings and text (in Bangla and English) on the pages often reveal fissures of conversation and intimate stories.

Being a Bengali, Chatterjee understands fish as a center of cuisine and cultural caricature very well as he played with both in his Mejobabu’s Diary (Fig 7). The narratives move with the dak naam of the fish, pieces of toys sometime in the corner of a cupboard, sometimes in muddy water. The last page of the diary reveals that Mejobabu died. Inspired by Dorothea Lange, he justifies that his imageries appear in defense of the words and notes, which take us to the parallel realm where he replies to the call of acts and memories from his surroundings. He explores the pictorial languages of watercolor and photographs to draw and write and allowed the lines and forms to flow in the texture of handmade paper. The images and texts play the role of each other’s contemporary. Each page of his book tells a different story, an attempt to answer the call of his imagination by drawing the thread between reality, belongingness, and memoir.

Baishali Ghosh teaches art history at the University of Hyderabad. Her research explores migration theories and material culture, investigating the process, production, and circulation of the South Asian imageries.

The author and artist wish to thank Amit Viswakarma & Rituparna Roy, whose work photographing & archiving the Dak project was crucial.