by Francesco Parisi

Francesco Parisi is an associate professor in Cinematography, Photography and Television at the University of Messina. His principal areas of interest are media theory and cognitive approaches to visual culture. He has recently published a book on these issues: La tecnologia che siamo (The Technology We Are), Torino, Codice 2019.

In a commencement speech to Kenyon College, David Foster Wallace tells a story that sounds like this:

“There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

This little story, probably inspired by one of Marshall McLuhan’s many sallies, is perfect for making clear how being immersed in a (media) environment produces the medium’s disappearance. Fishes know nothing about water, as the hunter-gatherer knows nothing about air, and we today, mutatis mutandis, know nothing of what splashing around in the digital environment implies.

Let me explain myself.

When the coronavirus epidemic started, I was among those who badly tolerated the idea of a lockdown. Let me be clear: it was not easy for anybody, but I was impressed by how quickly we stopped thinking and started shouting to each other to stay home, renouncing fundamental aspects of our daily life. Lockdown was not just about preserving health, but was a violent attack on reason in the name of safety. Practically, this manifested in many circumstances: I witnessed the media pillory The Runner (the authentic archetype of the irresponsible); I saw scuba divers getting a fine; drones twirling; helicopters patrolling desert beaches; and many other circumstances that I don’t know whether to define as hallucinatory or grotesque. But above all, I saw as far as a citizen can see within his/her infosphere (Whatsapp, FB, News, whatever) the nearly uncontested rise of the hashtag #IoRestoACasa (IStayHome), the synthesis of a paternalist, single thought impermeable to any kind of criticism.

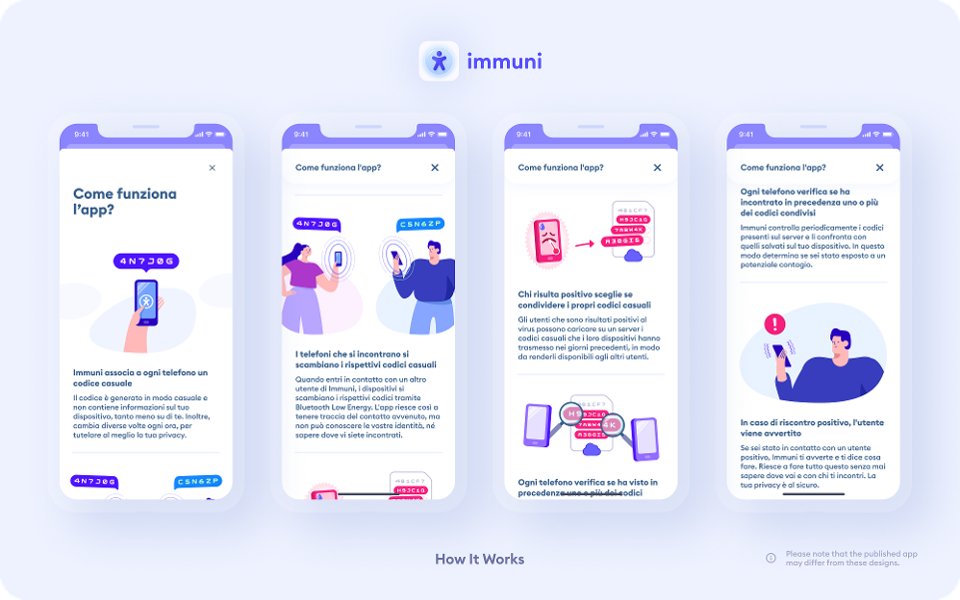

When the Immuni app for tracking covid-19 began to be discussed, the scenario looked like it came from an Orwellian novel. In the beginning, the idea of the app disturbed me instinctively, as a further kind of restriction. But then, after having read some articles and having seen some things happen, I began to doubt my initial response, and I changed my attitude. I started noticing a surprising and unexpected analogy in the way of thinking between those who unilaterally invoke total closure and those who don’t want the app. I was impressed, in other words, by the parallel between the form of reasoning of those cheering to stay-home-and-stop and those who today alert us about the app-as-dictatorship.

What do these two forms of reasoning have in common? The fact that they are both based on ideological or emotionally-driven positions, and not grounded on rational evaluations of complex variables. You can’t go out because-this-is-correct; you can’t use the app because-it-threatens-our-privacy. Both arguments are, so to speak, resistant to actual circumstances; they are irrefutable because they rely on dogmas or emotional states more than careful evaluations. Let us for the moment set aside the freedom of movement and focus on data control. There are two ways, in my opinion, to face the discussion about the app: the first is to evaluate the complex scenario that would unfold and carry out critical analysis based on the constant and exhausting negotiation between security and privacy. The second is to close any discussion even before it starts, either by drawing on historical precedents that corroborate futurist theses or by premediating hypothetical scenarios that should foresee what will happen.

For the first way, issues linked to the full accessibility of the code (open source), the kind of technology employed (centralized or decentralized), integration with other European countries and with the project started by Google and Apple, the temporal delimitation of the phenomenon, are all fundamental and deserve to stay at the very center of the discussion. Also, they have to be explored by different perspectives and by people with heterogeneous competencies (IT, anthropological, psychological, philosophical, medialogical, and political). An example is offered in this article. For the second way, all this is out of the agenda since the beginning.

Here I don’t want to offer a solution to whether you should or should not download Immuni—in line with the anti-dogmatism I am defending—but instead to provide some methodological tips to avoid being like the fish of the opening anecdote and to be able to regulate the relationship between natural environment and media environment, between organic life and digital identity. The recipe is straightforward and relies on two concepts: trust and awareness.

Trust. If as a citizen I demand to be treated as such and not as a trained monkey, I have in my turn to treat the State as a Republic and not as a dictatorship. It is a principle of reciprocity which, for intellectual honesty, I don’t want to escape from. It does not matter that trust has been shockingly disregarded so far: chasing runners on the beach, to me at least, does not suggest the idea of a State which faces an emergency rationally, but a State which applies an obtuse model without adequately evaluating the consequences. However, trust is always an essential condition in any civil negotiation. Trust in institutions has to be fostered and not undermined, and it has to be demanded even if we do not always show that we deserve it.

The same can be said towards our fellow citizens. Observations like if-one-does-it-everybody-does-it, or Italians-are-uncivilized-so-you-can’t-trust-them, are not only logically unfounded but function as causes of their own. In fact, if I picture a State that nails me down in the house and forbids me to walk alone outside in a space with no other inhabitants, against reasonable thinking, and I picture my fellow citizen as a miscreant waiting for the occasion to misbehave, how can I ever act for the interests of the citizenry at large? I will be frustrated and pissed off, instead of being responsible and sympathetic. I will be induced to stop thinking by zoning out on the couch or on the Internet (if I have them, of course) or by transforming myself into the wrongdoer I am afraid of, just to not succumb to frustration.

Awareness. Trust alone is not enough. After all, we are citizens, not kids. If a kid can entirely trust in somebody who looks after them, a citizen has always to be informed and aware. First, we have to require the Immuni app to be the best possible technology it can be, by demanding it to satisfy some non-negotiable prerequisites. As far as I am concerned, these prerequisites are: the full accessibility of the code and that the app could be accepted only within a specific, agreed-upon and predetermined timespan. Other requirements can be chosen after an extended negotiation between the parties.

The temporal aspect—the concern that we will be slaves of the app, should it enter the scene—is undoubtedly the one instilling the most worry. The argument made by the people who fear this case typically sounds like this: exception-in-emergency-becomes-the-norm. Here the shape of reasoning traces that of the staunch lockdown at home: to detect a working principle as a plausible hypothesis and to transform it into an inescapable condition. Usually this concern follows the exposition of cases from the past and/or the representation of futures states that make us see for ourselves the risks we run (premediation).

Privacy is, naturally, the object of the dispute, as well as the control coming from its violation: I take care of my privacy; I don’t want somebody snooping around my daily activities! Usually, to people thinking like that you can suggest, very placidly, that privacy is a liquid and relative concept, a point well illustrated by the story of the fishes. Indeed, which privacy are we talking about? Tastes? Political ideas? Friendship network? Domestic rituals (aka stories)? Sexual orientation? Medical records? Clouds so-that-everything-is-synchronized? Credit cards wiped here and there? Chats? Watches measuring one’s heartbeat? We are already data; we are already information bought and sold. Therefore, abstractly rooting for the ideology of privacy is naive in the best case and dishonest in the worst.

At this point, the most resourceful, those with a creative flair, reply: what does that have to do with anything, in those cases I gave my consent. Or: it is one thing to give our data to American companies that are cool and protect them (the wrongdoings of Cambridge Analytica and other data leaks, apparently, did not weaken this belief), but another thing to giving them to a government that can limit my rights and act, through police, on my freedom. And the slippery slope starts, so that, according to this logic, within one year we will be forever under surveillance. Amen.

Why do I maintain that the concept of privacy is liquid and relative and that we necessarily need to be aware of that? Because the split of the individual into an organic body and a media identity is a problem that has preceded, for some time, contemporary circumstances. Like the young fish in the water, we are born blind about the externalizing condition that technologies reproducing reality have originated. When photography—the first technology reproducing the world bypassing human intervention—was invented, reactions were very different and covered a vast emotional repertoire. Enthusiastic exaltation and terrible fear went with the rise of the technical image in nineteenth-century Paris. For the first time in human history, it was possible to save a reflected picture of the self, a specular double that would have been preserved photographically, escaping space and time.

The face became merchandise because its exclusive control would be lost forever: with photography we have relinquished the property of our own body’s visibility. The invention would have produced a Copernican revolution in control techniques. And it did so: Alphonse Bertillon in Paris created the standard still used today in mugshot photography. I leave you to judge if this is bad or good. The news here, though, is that not everything that then sounded good, necessary, orthodox, indispensable and fully achieved endured until today. Physiognomy, for instance, had an extraordinary flowering and scientific accreditation in all Europe, just to be branded as pseudoscience some years afterward.

In this sense, then, privacy is liquid and relative. Many Parisians of the nineteenth century felt photography was outrageously wrong. For others, it was extremely intriguing. Such forces counterposed each other and shaped the new externalizing mediascape that we now swim in like fish in water. Since then, many other technologies of reproduction have entered the scene. If we focus on the Immuni app, if we converge all our intellectual resources on a single object-process, then we completely lose sight of the sea we are immersed in. This exercise of awareness has to drive our critical judgment in the evaluation of media circumstances. We are not just bodies living in space, we are also avatars circulating in the electronic sea.

Rejecting the use of an app on the basis of arguments that isolate it from the media context makes us like fish that ignore the water. Because if we believe that having access to information is a right, that interacting through interfaces with other human beings is an irrevocable accomplishment, that watching or even influencing the world from your chair is an achievement, then we must be willing to negotiate by making ourselves adequate to the pressures that these possibilities imply. We must act carefully, though, because being adequate (ad-aequare) means to be peers, not subjugated. It means becoming perceptually and cognitively aware of the environment, and to act, only then, politically.

There is another alternative, of course: it is the one of the fish who, tired of the water, started to desire the air…