By Ching-In Chen

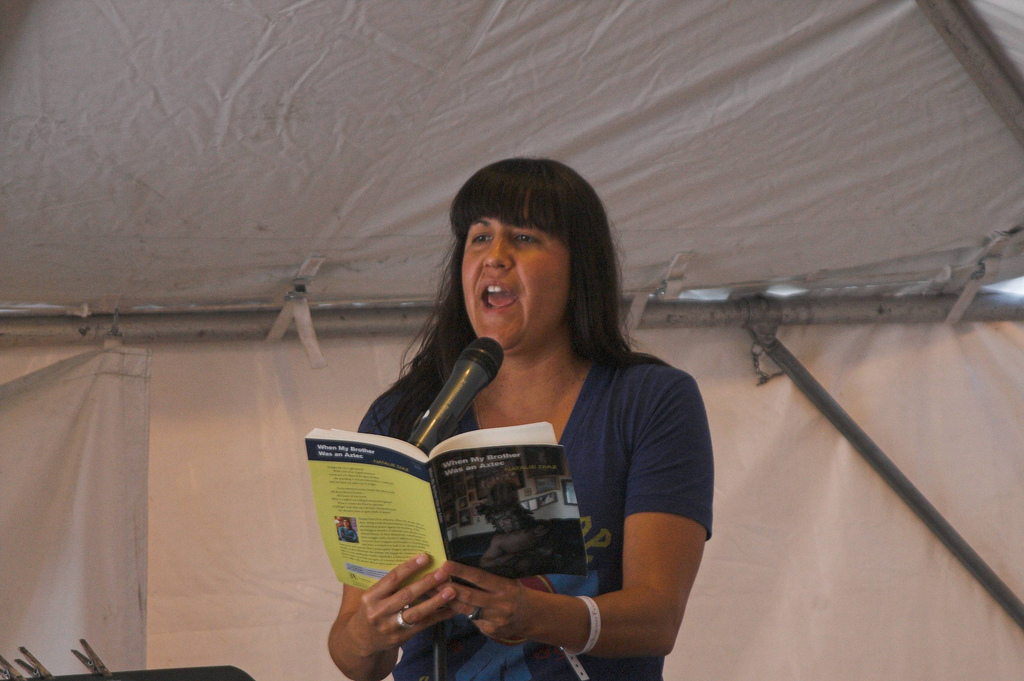

Natalie Diaz recently visited Milwaukee, Wisconsin for the 20th Anniversary Returning the Gift (RTG) writers’ conference. I was excited to meet her after hearing so much about her work and words and was grateful that she made time to chat with me about her book, When My Brother Was an Aztec (Copper Canyon Press, 2012), and her writing.

Ching-In Chen: I had my students read your abcedarian, and we’ve been talking about

structure and content in class, and the connection between the two. So this question is for them: why do you choose to write in form, and is it a choice you make related to your content, or something else?

Natalie Diaz: I like the tease of form, the tease of control it flashes at me when I start a poem. There is an almost-promise of rules and a rein that will help me harness all of the fast and loud of my emotions in my head.

But, at least for me, when I start moving around in form, start pushing and pulling at the structure, I realize that I can control it more than it can control me. I think the very idea that form poetry is controlled or has rules somehow gives me permission and power to break it down and make it submit to what I need it to be. Ironically, I’ve found form poems to be the places where I am the most free on the page.

Sometimes I abandon the form after it has given me a few lines. Starting out in form lets me see what my poem is made of and also lets me see if the form can handle what I’ve got to give.

We tend to see form as this giant door with a million keyholes and bolts and latches to keep us out, but once we get past that, there is so much room and space to explore, you can walk into the kitchen and break all the dishes, or build a fire in the sofa, or make love in the library, or punch a hole through the hallway wall.

CIC: This idea of the house is actually one that I’m using to help my students think about content vs. structure — and I appreciate how you relate form to that. Did you intentionally set out to construct this running narrative thread about your brother? Are all these poems different rooms in the house that are related?

ND: I’m glad you asked this, because I keep getting questions asking about the third section of my book…

The way I see my book, is that I’ve invited my readers to a place, the place of me, the place of my living. It was important for me to give voice to all of the “me” that exists in me. While a large chunk wanders or runs or struggles through the landscape of the reservation, another large chunk invites you in a little more, into the houses of me, and this is where you meet the brother who figures so deeply or darkly into my work, and then, finally, I take you by the hand and lead you maybe into my room or into my chest, to see more, maybe not much, but more of me. Who am I and what do I do in the midst of this place and people? I certainly don’t stop.

Some people feel like the last section of my book doesn’t match or fit with the first two sections, because they are looking for despair, maybe. But, the last section of my book is the carrying on that we all do. The surviving. I can grieve and make love at the same time. Maybe that is how I grieve.

CIC: I was actually going to ask you about the last section of the book. Not because I thought it didn’t fit with the rest, but because it seems to be the most vulnerable, almost the most hungry part of the book, and I was interested in the choice you made to place those poems where they were.

ND: The epigraph at the front of my book is very important to the collection, in my head anyway. It means that no terrible thing can last a hundred years, or that at least no body that can resist or last through that many terrible years. And well, that third section is the body resisting. The bodies. Carrying on. Maybe not doing it well, but doing it.

CIC: Isn’t it also about the terrible things we enact? I’m looking at that line, “I am what I have done – ….” in “Self-Portrait as a Chimera.”

ND: Yes, it’s about the terrible things we are part of, that we cannot separate ourselves from.

Yes. We do and do and do. What horrible creatures we are to watch human suffering and do nothing. Or to justify the little to nothing that we do. Or to go on.

Some mornings, I think, Natalie, who are you to go into this bright day and love and smile when people are dying and suffering all over the world.

One of the poems in that section is about making love after watching the news about the war.

CIC: So, why write poems? What do poems do, if anything, or what do you want your poems to do?

ND: I don’t have great expectations for my poems outside of my own head. They function almost like prayers for me, they allow me to ask and beg after the things I don’t understand, the things I am afraid of. And like with prayers, I have never expected an answer.

Of course, I am aware of how they can function outside of me, but they are a truly selfish impulse. I write because I don’t know how else to make sense of the things that wake me at 2:30 a.m. gasping for air or the thing that makes me have to push and pull myself through mere minutes of certain afternoons. I think my poems are my attempts to understand the animal that I am. To understand how to, and this hearkens back to an almost conversation you and I had, how to live with the monster that I am. That we all are.

Now, in a revision stage, yes, I consider my audiences, my readers, and with this first book, I considered my community, here at home. But these concerns all come in later, not when I am pushing my fingers into a poem or wandering around and peeking into its windows.

CIC: How did your consideration for your community enter into your revisions?

ND: I don’t mean that I edit based on their expectations, when I say revisions … I just mean that I consider them, what they can come to easily in my work, what voice they might recognize, what they might see of themselves in what I have had the opportunity to write and share…

CIC: Is there also a challenge in there, about trying to provide an alternative vision, or is it more about reflecting what you see back to them (or both, or none)?

ND: I think it goes beyond all of that, what my responsibility is to my community as a writer, my tribal community, my spanish-speaking community, my small desert town community … my responsibility is to write, to say, to not shut my eyes no matter how it might make people feel, to write the things I need to write, to not hide my voice.

That is the only responsibility I feel, at least, right now, that is the only responsibility I feel.

If I can do it, they can do it. This applies to writing, to playing basketball, to learning my language, etc.

CIC: You mentioned the language, and that was a topic I was interested in chatting with you about. Does your work with the elder speakers of the Mojave language enter into your poetry or impact your use of language in your poems? I noticed that Spanish surfaces much more in these poems.

ND: I have a few poems in the book that use Mojave language, but our Mojave language was silenced by English for so long, that I never want to force it to speak English for me. What I mean by this is that I will say English things in English, and I will say Mojave things in Mojave. I use Mojave to say what I cannot say in English, truly Mojave things that are too strong or too heavy for English to carry.

But the work I do, and this knowledge and knowing of my Mojave language has changed my writing in that I have a new way to come to language, to words, to the emotions or questions I am trying to express. Spanish offers me this as well.

CIC: So did writing this book change the way you come to language and words?

ND: I think writing this book is the way I came to words during these poems. This is the way I talk, this is the way I know the worlds I live in. There are a lot of mouths and hands in the book … these are how I filter the world.

CIC: So, what are you working on now?

ND: Robert Hayden essay. My second manuscript. A short story collection.

a half glass of wine

working on waking up in the morning

language wise, a digital and print dictionary, a high school language curriculum…

CIC: How is your second collection shaping up? Is it similar in theme and style, or a departure from your first book?

ND: This book is different primarily because I am home now, writing it, instead of being away and writing about home. I am back in my desert, my landscape, with a new language… There are themes that are connected to the last book, and I still play with form, but, it feels new to me, it feels more like this place where I am, more river, more wild, more shotgun sky.

But, I’m letting it breathe the way it needs to breathe, I’m not trying to tell my poems which direction they should walk or run …. they are happening, and I let them.

***

Natalie Diaz grew up in the Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California, on the banks of the Colorado River. She is Mojave and an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community. After playing professional basketball in Europe and Asia for several years, she completed her MFA in poetry and fiction at Old Dominion University. She was awarded the Bread Loaf 2012 Louis Untermeyer Scholarship in Poetry, and also received a 2012 Lannan Residency. She currently lives in Mohave Valley, Arizona, and directs a language revitalization program at Fort Mojave, her home reservation. There she works with the last Elder speakers of the Mojave language.

Ching-In Chen is author of The Heart’s Traffic and co-editor of The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities. They are a Kundiman, Lambda and Norman Mailer Poetry Fellow and a member of the Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation and Macondo writing communities. A community organizer, they have worked in the Asian American communities of San Francisco, Oakland, Riverside and Boston. In Milwaukee, they are cream city review’s editor and involved in their union and the radical marching band, Milwaukee Molotov Marchers.